So, how did you get your jobs?

Becoming a scientist or working in science is never a straight forward path: appreciation of the natural world, hobbies, high school jobs, science fiction and random life events all come into play. We discuss these sinuous paths into science with a special live audience, The Field Museum's Youth Design Team summer interns. We hope that our stories were a source of science and fishy inspiration!

Youth Design Team

The Youth Design Team (YDT) is part of the TakeThe Field programs here at the Museum and is designed in collaboration with the Pearson Foundation's New Learning Institute. YDT takes teens behind the scenes to interact with scientists, designers, media producers, researchers and other teen volunteers like themselves. Teens hear firsthand what it is like to roam the plains of Africa and tromp through the forests of South America. In addition, they participate in the process of designing an exhibit from scratch!

Episode 15: Exploring Collection-Based Research

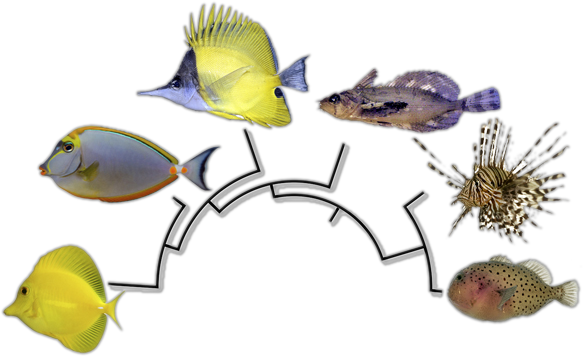

In our last episode, we discussed the role of collection data for scientific investigation. In this episode, we explore the value of the research on museum specimens and artifacts themselves, focusing on the use of specimen examination and evolutionary hypotheses to better explain the natural world. To help us discuss this topic, we are pleased to be joined by Dr. Peter Makovicky, The Field Museum's own Curator of Dinosaurs and Chair of the Department of Geology. Phylogenies (a hypothesis of how life is related evolutionarily) are crucial for predicting the distribution of incompletely studied organismal characteristics ranging from the presence of venom in fishes, to feathers on dinosaurs, or how the anatomy of eyes change in the deep sea as a result of selective pressures. In other words, knowledge of the evolutionary relationships of life allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. Museum collections are a critical component of this work, from the initial collection of samples used to infer our hypotheses of how life is related (e.g., whole specimens, tissues used to extract DNA for genetic work) to our ability of accessing this material again to test and explore evolutionary hypotheses.

An example of the biological questions we can explore in this manner is tracing the evolution of venomous fishes. By looking at venomous fishes from an evolutionary perspective, we generated a much more accurate picture of fish venom evolution than was previously suggested using a strictly observational approach. To explore venom evolution, we began by taking a major stab at the fish tree of life by analyzing all suborders and known venomous groups of spiny-rayed (Acanthomorpha) fishes for the first time. Using the resulting family tree of fishes as a framework, we mapped the species that were known to be venomous on to this DNA-based tree. This provided an initial estimate of how many times venom evolved and allowed us to predict which fish species beyond the "knowns" should be venomous or could possibly be venomous. To test these predictions, we explored the museum collections and dissected scores of specimens to look at the detailed anatomy of fish venom glands and clarify how many times venom evolved on the fish tree of life. By working our way down the fish tree of life by comparing ever more distantly related fishes from the known venomous fishes, we could pinpoint the number of times venom evolved, the exact groups of fishes that are venomous, and revise the identity of venomous fishes. This type of research is occurring world wide based on the collections at The Field Museum, and similar institutions that house, maintain, and allow access to museum specimens for scientific research. This example is just one of the many stories surrounding research done at The Field Museum with collection-based research.

Piecing Together the Mysteries of the Fish Tree of Life

One of the primary reasons that we here at What the Fish? are fascinated with the evolutionary history of life on Earth is that it provides a context and scientific hypothesis from which we can further study the wonderful biodiversity of fishes. For example, if we have a working scientific hypothesis of how different species of clownfishes are related to one another, we can address questions surronding the number of times clownfishes have formed symbiotic relationships with anemones. But how do we build these evolutionary trees of fishes, such as the one seen below? Well there are various different kinds of scientific data that can be used to infer evolutionary relationships through time (e.g. variation in the sequence of DNA/genes, anatomical features, behavioral traits) that scientists around the world collect in order to support these hypotheses. Shared anatomical characteristics, such as the position of a spiny-rayed dorsal fin, may be indicative of common evolutionary ancestry, and scientists use this evidence to produce hypotheses regarding the evolution of life on Earth.

A Fish Can Be Encased in Armor?

Although they vary in size, morphology, and type (e.g., plates, scutes), many fishes have evolved thick armor-like scales that help protect them from their aquatic environment and potential predators. Many fishes that live in and around the bed of aquatic environments utilize armor to protect their bodies from loosing scales as they burrow and scrape along rough substrates and potentially rocky or jagged environments, such as catfishes and poachers. Other armored fishes may sacrifice mobility for a tank-like body that makes them nearly inedible to nearby predators. For example, the aptly named boxfishes have scales are hexagonal in shape and result in an armor that looks like a bee's honeycomb. The body armor of fishes are so effective that various scientists and researchers have been investigating the morphological properties of fish scales, such as those in bichirs, to aid with the development of stronger body armor for humans!

Have you ever swam at your favorite local spot and encountered a piranha? Believe it or not, this happens across North America all the time - not just in late night B-movies! So how does a fish that is native to South American freshwater rivers find itself living in a Missouri pond? Often these invasive species (a term that describes biodiversity that is introduced into a non-native environment and locale) are simply dropped off by pet-owners that are releasing them into the wild. In some cases invasive species take hold in a non-native environment purely through accidental circumstances. Occasionally, invasive species are purposefully placed in a locality because someone thought they would serve a specific positive purpose. For example, mosquitofishes (Gambusia affinis) have been frequently introduced in non-native habitats because people wanted them to control mosquito populations. Join us and our special guest, Caleb McMahan, as we discuss this environmentally important topic.

Introducing non-native species frequently has negative effects for the local environment and biodiversity. Invasive species can dramatically alter the fragile ecosystems they are introduced into and severely threaten native wildlife. One example of an introduced fish that has reeked havoc on the native fishes of Illinois is the Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus). The Round Goby was introduced into the Great Lakes (including Michigan) through freighter vessels traveling from the Black Sea. Once the Round Goby was accidentally brought to the lakes they began spreading at a rapid pace.

Unfortunately, the increase in these invasive gobies has harmed many native fish populations, such as the Mottled Sculpin (Cottus bairdi). Round Gobies are voracious predators on the eggs and fry of other fishes and they are fiercely territorial with their spawning sites. This creates competition with native fishes for reproductive space. Another invasive species in Illinois is the Grass Carp from Asia (Ctenopharyngodon idella), which was purposefully introduced in the United States in an effort to control aquatic weeds. The introduction of the grass carps into non-native habitats was carefully controlled, and many of the introduced populations were gentically modified to be sterile in an effort to curb unwanted population growth in the wild. Despite these precautions, populations of Grass Carp have spread across the United States since their intial introduction in the 1960's.